Difficult and Exhausting

How a “Simple” Thing Like an Exhaust System Can Create Deadly Difficulties

By James Williams, FAA Safety Briefing Magazine Associate Editor

It seems so simple: just a metal tube to safely carry hot exhaust gases away from the aircraft. What could possibly go wrong?

As it turns out, quite a bit. General aviation (GA) exhaust system failures have been indicated in many accidents over the years, leading to concern from the General Aviation Joint Safety Committee (GAJSC). Between 2011 and 2019, 23 GA accidents and incidents involved exhaust systems. This isn’t a new concern. National Transportation Safety Board (NTSB) recommendations date back to the 1980s concerning exhaust systems, and prior agency concerns are documented back to the 1940s. That said, it’s important to recognize that the solutions to these difficulties are a mix of modern technology and old-fashioned upkeep.

There are three general types of exhaust failures: muffler failures/blockages, exhaust leaks causing noxious gases or fumes to permeate the cabin, and exhaust cracks causing heat damage and/or fire. While there can be some overlap among the three, this framework offers a helpful way to think about preventing an exhaust-related accident.

All Blocked Up

We may scoff at calling the exhaust parts of the powerplant a “system,” but it is more than just a bunch of crudely welded pipe sections. In highly competitive environments like Formula 1 racing, the exhaust systems are an area of an intense engineering competition. The racing teams continually try to maximize output while minimizing weight with exhaust system designs. The competition got so out of hand that officials had to limit the number of exhaust systems the teams could use per season. While our GA aircraft exhausts are not nearly as refined, the same principle applies because even small constrictions or blockages can cause degraded performance or worse.

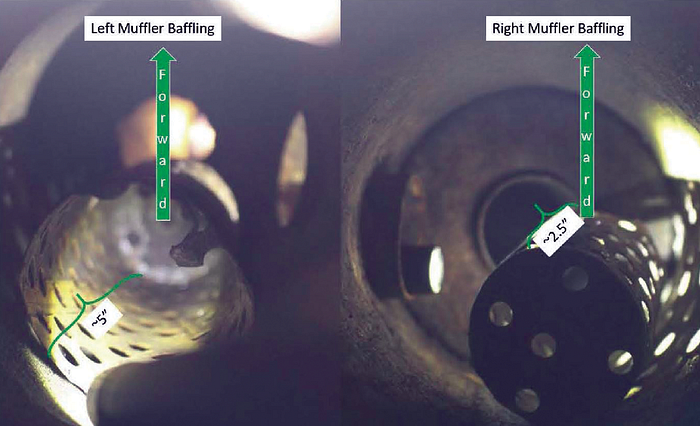

The unfortunate pilots of an amphibious Maule M-7 in Oregon found this out in the worst possible way. After an uneventful taxi and run-up, the pilots began a takeoff on a paved runway and lifted off with about 1,000 feet of runway remaining. The airplane struggled to gain altitude once it departed ground effect, and the pilot realized they would not clear the 50-foot-tall trees on the other side of the river they were approaching. The pilot decided to attempt a water landing but failed to retract the wheels on the floats, causing the airplane to nose over into the water. The pilot was killed, and his passenger received minor injuries.

The ensuing investigation revealed that both mufflers had suffered broken baffles, and the baffling in the right muffler had managed to rotate 180 degrees from its intended position, reducing exhaust flow from that muffler by 89%. The NTSB concluded that the loss of power caused by the separated baffling was the probable cause of the accident.

Out Cold

One of the fears I acquired during my flight training was the use of cabin heat. No matter how cold it was, I always had an unwarranted fear of sliding that lever over and enjoying one of nature’s great ironies. While internal combustion engines are great at providing propulsive power in a space and weight-efficient package, they aren’t great at transforming their fuel into kinetic energy. Most cars probably only convert 30-ish percent of that available energy into work, while our technologically less advanced aircraft piston engines are likely dipping into the 20s. But this major downside comes with one key advantage, most of that energy is transformed into “waste heat” that we can harness. My fear arose from how we harvest that heat. Generally speaking, many GA airplanes use a shroud that wraps around the muffler to circulate outside air around the hot part and then into the cabin. In theory, it’s a great system that recycles “waste heat” into a warm cabin at no cost to performance and with no additional fuel burn.

As the saying goes, though, there’s no free lunch. The drawback to this marvelous act of recycling is that any crack or leak in the muffler area covered by the shroud would allow exhaust gases, and most critically, carbon monoxide (CO), into the cabin. CO is an odorless, colorless, and tasteless gas that very easily bonds to the oxygen-carrying system in the blood at a far higher strength than oxygen. This means that once CO locks on, that red blood cell can no longer take oxygen from the lungs and to the rest of the body where it’s needed. This impairs your ability to function and can ultimately be fatal even if you aren’t at the controls of an airplane. That’s why it was always a risk-reward calculation between cabin comfort and CO risk.

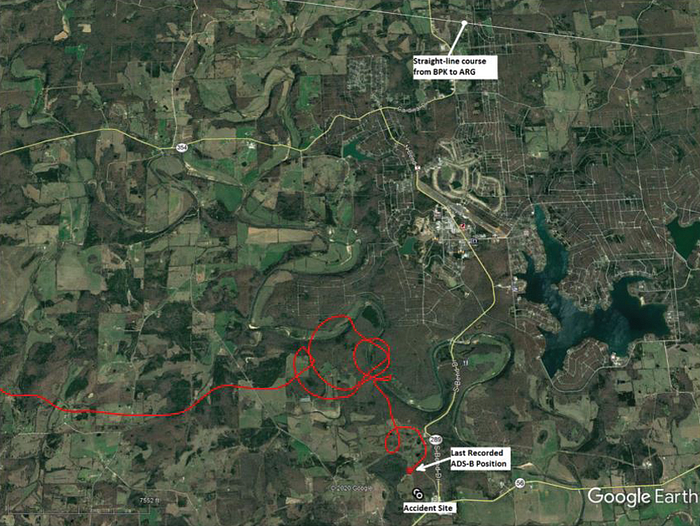

Unfortunately, a flight instructor and a private pilot ended up on the wrong side of that calculus in late 2020. The instructional flight departed from outside Little Rock. It made a brief stop at an airport near the origination point, then flew up to northern Arkansas over a couple of airports before turning east southeast and requesting an IFR clearance to Walnut Ridge Airport (ARG) from Memphis Center. After initial radar and radio contact, the flight briefly proceeded before radar contact was lost and radio contact became intermittent. Efforts to contact the missing flight by ATC and aircraft in the area continued, but to no avail. The flight continued, but not directly toward the destination airport. The flight’s last seven and a half minutes were an increasingly wobbly and looping mess ending just south of Franklin, Ark. The ADS-B track looked like a VFR into IMC accident despite it being clear below 5,000 feet above ground level (AGL) and 10 miles of visibility in daylight conditions.

Both pilots were killed, and the NTSB examination of the wreckage determined that there was cracking in the muffler that predated the accident leading to CO poisoning. Toxicology reports from the flight instructor confirmed this finding.

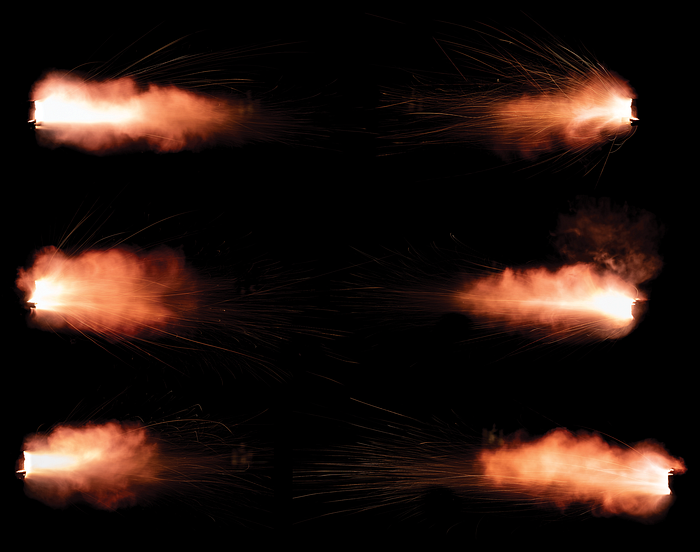

Fire in the Hole

The last group of accidents is the one that really captures our attention: Fire. I’ve long known that fire is the one thing that truly scares me in aviation. Don’t get me wrong: many potentially dangerous situations deserve consideration, but fire occupies a special place in my mind. Faulty exhaust systems can either be a direct source or create a source for fire. Many components in the engine compartment can be sensitive to high heat, including wiring and fuel lines (both of which can lead to fires if damaged).

There are three general types of exhaust failures:

1) Muffler failures/blockages

2) Exhaust leaks

3) Exhaust cracks

The pilots and passengers of a Piper Malibu Mirage encountered such a situation. Thankfully no one was killed, but unfortunately two of the five on board suffered serious injuries when the airplane caught fire in 2018. Immediately after takeoff, the pilot noticed an odor of smoke. After a very brief attempt to troubleshoot the issue, he decided to turn the aircraft back to the airport. At that point, smoke began to pour into the cockpit. Shortly afterward, the engine made a loud noise, the oil pressure dropped to zero, and the engine lost all power. The pilot determined it was impossible to reach the airport and made a forced landing in a field. All five occupants were able to exit the airplane and get clear as the fire burned the forward section of the airplane in front of the cockpit. The local fire department arrived quickly and extinguished the blaze before it spread to the rest of the aircraft.

The NTSB investigation determined that the aviation maintenance technician (AMT) completing a service bulletin on the exhaust system immediately preceding the flight failed to follow proper procedure when reassembling the exhaust leading to the leak and fire. Contributing was the AMT’s supervisor, who failed to oversee the process and relied on a post-maintenance inspection where the error would not be visible.

Easing Your Difficulties

So what are we to do? It takes a mix of diligence, teamwork, and technology. The first and easiest thing to do is step up your preflight of the engine compartment. Look for obvious damage to the exhaust and indications of wear, damage, or staining to nearby components. This can be an excellent way to catch small leaks that can lead to larger cracks. If it’s an airplane you fly regularly, consider taking periodic photos of the engine compartment so you can compare them. With almost everyone carrying a high-quality camera in their pocket, it’s an easy way to detect slow-moving trends. That way, you have a basis for comparison when something looks off, but you can’t remember if it was that way last time. This might not work as well with every airplane but doing the best you can to get a good view of the compartment (like using a flashlight) improves your odds of avoiding adversity.

The next step is to team up with a good AMT and work out a plan. At what interval is your exhaust system inspected per the service manual? What does that inspection include? Do you and/or your AMT feel that is sufficient? There is no requirement to inspect the inside of the exhaust during a 100-hour or annual inspection using a borescope or other means. While we tend to think of an exhaust as a permanent part of our engine, perhaps that thinking should shift to view it as an exceptionally long-lived wear part. Look at it more like brake pads or tires; monitor the exhaust system’s condition carefully and replace items before a failure. You may want to talk to your AMT about setting a schedule for periodic inspections and add that item to the nearest annual, 100-hour, or another shop visit. This practice might add a bit of downtime and cost, but it’s money well spent.

Another thing you and your AMT can do is report any issues encountered to the FAA’s Service Difficulty Report System (SDRS). The SDRS (sdrs.faa.gov) allows the aviation community members to upload a report if they experience an issue with a part. It allows the FAA to collect data on service issues before they lead to accidents. Gathering data on some component failures during an accident investigation can be difficult. Having trained with accident investigators, I find it truly amazing what they can determine from what appears to be bent metal. Even so, there are usually limitations on what they can categorically declare, especially in cases of fire where much of the evidence may be consumed. Having information from much earlier in the failure chain provides a better look at the cause of the failure and how it might be prevented. GAJSC has struggled with a lack of data on exhaust failures so catching them early is critical.

With GA aircraft exhaust systems, even small constrictions or blockages can cause degraded performance or worse.

The final leg of this triad is technology, particularly CO detection. CO detectors aren’t new. But the ones that I was most familiar with were the little orange dot that was usually affixed to the panel; it would change color in the presence of CO gas. While they certainly work and are very cost-effective (in the vicinity of $5), these devices lack any kind of alarm, meaning you must actively scan them. Paradoxically this means that if CO is potentially impairing you, you must actively monitor a small dot on the panel while continuing all your other tasks. That is precisely the kind of thing that CO poisoning makes more challenging.

Modern CO detectors come in wide varieties; most include an audible alarm and/or visual annunciation, so you don’t have to actively monitor them. Some will even log CO levels during flights in reports that you can access later, allowing you to detect small changes over time that may be below the levels that cause impairment, but that could indicate the start of a problem. There are both installed and portable options. One headset manufacturer has even integrated a CO detector into one of its products. You can also find CO detectors integrated into portable ADS-B In units. So even if you only rent airplanes, there are still plenty of options. They are available at many different price points, so a modern CO detector should be a part of your aviation kit every bit as much as your headset and electronic flight bag (EFB). Even the most expensive CO detectors are very cheap insurance against CO impairment.

Through these three methods, we can help reduce exhausting difficulties for you and the rest of the pilot community, making the skies safer for everyone.

Learn More

James Williams is FAA Safety Briefing’s associate editor and photo editor. He is also a pilot and ground instructor.